Nam

Stories

INDEX

Background sound track - "Radio First Termer" -

The Dave Rabbit radio show was an underground

"outlaw" radio show in Vietnam during the war

-

THE VALLEY OF CROSSES - French and the Mang Yang Pass

-

TRAILBOSS - Quads of Btry E, 41st Artillery

-

Gift of Joy - US servicemen's donations help the Montagnards

-

Pit Viper is KIA - 589th engineer bitten by snake

-

Bits + Pieces - From the 25 March 1971 ARTILLERY REVIEW

-

REBELS WITH A CAUSE - Kit Carson scouts called 'Chieu Hoi'

-

Highways to Peace - US Army Engineers pave Vietnam's highways

-

Going Where the Action Is - 1st Cav's move from the Highlands east

Reprinted from the

October 1971

"TYPHOON"

Courtesy of:

Pat Costello

Near

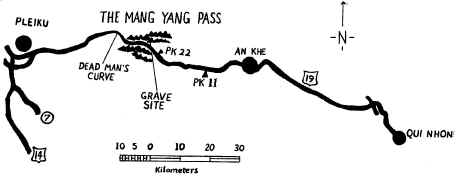

the border of Pleiku and Binh Dinh Provinces the Dak Pihao Mountains

tower above the surrounding hills and plains of the central highlands.

Highway 19, beginning at the coastal port of Qui Nhon, winds its way

westward to Pleiku through the highlands, passing through a narrow slit

in these mountains known as the Mang Yang Pass.

Highway 19 is one lifeline that feeds the allied forces operating

in the highlands at Pleiku, Kontum and the border camps. For years the

Communists have harassed traffic on Highway 19 and attempted to close it

on numerous occasions. Once, over 17 years ago, they did. The graves of

several hundred Frenchmen atop the northern rim of the Mang Yang Pass

bear mute testimony to the Communist victory. They died within a few

kilometers of their resting place.

The story of their battle has been recorded for history in the

fascinating work of the late French journalist Bernard B. Fall, The

Street Without Joy (The Stackpole Company-1964), from which the

following condensed account is derived.

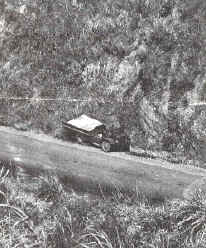

The Mang Yang looking toward An

Khe

Photo

credit: Baker

In 1953 the French were locked in a vicious struggle with the Viet Minh in Indochina. During the latter part of that year the Viet Minh conducted a successful offensive in southern Laos sweeping French forces out of the area. The Viet Minh withdrew but left two regiments of the Vietnamese People's Army, the 803rd and 108th, to conduct operations in the Vietnamese central highlands.

In July

a cease fire had stilled another Asian conflict in Korea. From there the

French High Command withdrew the Bataillon de Coree, made up of

volunteers who had served with distinction as an element of the U.S. 2nd

Infantry Division.

The battalion was dispatched to Indochina where additional units were added to bring it to regimental strength. On Nov. 15, 1953, the Korea Regiment was combined with the Battalion de Marche of the 43rd Colonial Infantry, composed of French and Cambodian jungle fighters, plus armor and artillery elements to form the Groupement Mobile (G.M.) 100.

On

New Year's Day 1954, the Group Mobile 100 departed Saigon for the central

highlands to assume the burden of the area's defense. During February the G.M.

conducted operations around Kontum where the presence of the 803rd People's

Army Regiment was being felt. After the Viet Minh overran outposts north of

Kontum, the G.M. withdrew to dig in at Pleiku. But after overrunning a G.M.

outpost at Dak Doa on Feb. 17, the 803rd disappeared into the jungle.

In

late March the 803rd reappeared in the south near the junction of Highways 14

and 7. The Group Mobile 100 moved south to meet the challenge. On March 22 the

803rd struck, hitting the G.M. in bivouac at Plei Rinh with mortar and

recoilless rifle fire. After a sharp, two hour engagement the Viet Minh were

beaten back, leaving 39 dead, 2 wounded and numerous bloody bandages on the

battlefield. The G.M. suffered 36 killed, 177 wounded and 8 missing.

"The two Viet Minh regiments in the central plateau area," noted Fall, "had now worked out their tactics in fine detail: unhampered by heavy equipment, unburdened by such matters as keeping open several hundred kilometers of road, they were able to move faster than any motorized force opposing them which by necessity had to operate from the peripheral roads."

Within a week, the center of action shifted north again to the area of An Khe where the Viet Minh had cut Highway 18 in the east. An Khe was held by Group Mobile 11, composed of lowland Vietnamese. Once again the Group Mobile 100 took to the roads, traveling 140 kilometers to the fortified camp at Pk 22 (i.e., Pleiku 22, the kilometer marking at the point 22 kilometers from An Khe traveling toward Pleiku) at the eastern entrance of the Mang Yang Pass. Their task was to keep Highway 19 open to An Khe.

On

Apr. 1 elements of the G.M. 100 were employed to open the road from Pk 22 to Pk

11 while units of the G.M. 11 provided security from there to An Khe for a

gasoline convoy. After the convoy completed its mission, the security units

began withdrawing from Pk 11 leapfrogging one another toward Pk 22.

At

3:30 p.m. as the units of G.M. 100 passed Pk 15 they were ambushed by two

battalions of the 108th Regiment. The French counterattacked and managed to

gain enough time to clear the road of wrecked vehicles, load up their dead and

wounded and pull back to the camp at Pk 22. The ambush cost the G.M. 90 dead

while the Viet Minh lost 81. The GM was now 25% understrength.

Despite

its weakness in the face of growing enemy strength, the G.M. 100 was sent back

to An Khe to relieve the G.M. 11. There it began digging in to prepare for the

expected Communist onslaught.

On May 8, 1954, Dien Bien Phu fell and a few days later the men of the G.M. heard the following broadcast from Viet Minh loudspeakers:

"Soldiers of Mobile Group 100, your friends at Dien Bien Phu have not been able to resist the victorious onslaught of the Vietnamese People's Army. You are much weaker than Dien Bien Phu. You will die, Frenchmen, and so will your Vietnamese running dogs."

It

became obvious that the G.M. without reinforcements could not hold An Khe, and

the order was given for its return to Pleiku. On June 23 intelligence reported

a Viet Minh force moving toward Highway 19 in the west. The G.M. 100 began its

evacuation on June 24 with Pk 22 as the objective of the first day's march.

The

evacuation began at 3 a.m. with the 43rd Colonials in the lead. The troops were

dismounted providing a screen for the vehicles.

At

Pk 6, the rearguard received sniper fire and at Pk 8 a soldier suddenly keeled

over dead, hit with a poison dart from a montagnard blow gun.

Rocks

on the Road

Shortly

after 12:30 p.m., a report was received from jungle commandos screening the

advance that Viet Minh elements were three kilometers north of the highway.

Around

2 p.m. the 43rd Colonials reached Pk l5 where a small plain covered with

elephant grass borders the road. They found rocks on the road, a sign of an

ambush, and sent out a company to reconnoiter through the elephant grass.

"The

Viets were here," wrote Fall. "The big, the final ambush to engulf

all of G.M. 100 was ready to be sprung. Vietnam's 803rd People's Army

Regiment had kept its promise. The main striking force was already in place,

its weapons poised, while the French were strung out along a road where their

heavier firepower could hardly come into play."

The

reconnaissance company triggered the ambush and the Viet Minh opened up with

devastating mortar and artillery fire. Within a few minutes the lead armor was

destroyed and the mobile command post knocked out.

Soon

the French ammo trucks began to explode under the Viet Minh mortar barrage. At

the same time, the Korea Regiment arrived, pushed through the wrecked vehicles

and linked up with the 43rd which managed to get a few of its vehicles running

and break out. But the Viet Minh quickly closed the ring. The Korea Regiment

formed a defensive perimeter and dug in. The B26 bombers arrived from Nha Trang

to strafe and drop napalm but the fighting was at close quarters now and they

were ineffective.

The

remanants of G.M. 100 were ordered to break out to Pk 22. When it became dark

the break out began into the dense jungle south of the road. There the G.M.

broke up into small units for faster movement and began its arduous trek.

During the night the G.M. suffered hundreds of casualties to Viet Minh ambushes

and the next day the struggle continued.

On

the morning of June 25 after 40 hours of almost continuous fighting, the

survivors reached the camp at Pk 22 held by the 1st Airborne Group. After the

stragglers were collected, the French pulled back to a Mang Yang Pass garrison

held by the Montagnard Mobile Group 42.

The

battle was not yet over for now the retreat began again from the Mang Yang Pass

to Pleiku. By June 28 the French were only 30 kilometers from Pleiku and had

entered an area of plains with tilled fields and villages bordering the road

when signs of an ambush began to appear. It was now the 108th Regiment's turn.

This

time the French were prepared to react when the first shots were fired. They

quickly formed a defensive perimeter with their artillery and vehicles in the

center. At 12:15 p.m. the Viet Minh infantry attacked the sector held by the

Korea Regiment, broke through and pressed on toward the artillery now firing at

point blank range.

The

Korea Regiment managed to counterattack, however, and with yells of "Coree" hit the Viet Minh in the flank. They were aided by the arrival of the

B26s which, for once, had the Viet Minh in the open. The Viet Minh were forced

to withdraw. On June 29 the convoy reached Pleiku.

Group

Mobile 100 was finished. Less than half of its more than 3,000 men made it from

An Khe to Pleiku. Virtually all its vehicles and equipment were destroyed or

captured. In five days of fighting the Korea Regiment had suffered more

casualties than in two years of fighting in Korea.

On

July 20 the armistice was signed at Geneva ending the First Indochina War. On

Sept. 1, 1954, the Group Mobile 100 was officially dissolved by the French High

Command.

A

few years later the 803rd and 108th NV A Regiments would return to the south to

fight another war.

At

Pleiku 15 a marker was erected with an inscription in Vietnamese and French:

"Here soldiers of France and Vietnam died for their countries."

Today's

Antithesis

Today

on Highway 19 an occasional wrecked deuce-and-a-half along the side of the road

testifies that the Communists are still here. But the situation is vastly

different from 1954. Highway 19 is no longer an unimproved, dirt road. Now it

is surfaced and allows vehicles greater speed.

An occasional wrecked

deuce-and-a-half

Photo

credit:

Baker

Military

convoys travel the road every day between Pleiku and An Khe. In addition to the

military traffic, there are green and yellow buses with

their roofs piled high with luggage and people hanging out the windows as well as

dump trucks, oil tanker trucks and motor scooters on the road often traveling

alone.

Guarding

Highway 19 from Pleiku to An Khe is now the responsibility of the 3rd ARVN

Armored Cavalry Squadron and U.S. Task Force 19.

The

3rd Armored Cavalry was organized on Jan. 1, 1954, the same day the Group

Mobile 100 began its ill-fated journey into the highlands. After the Geneva

Armistice, the unit moved south and became a part of the Army of the Republic

of Vietnam.

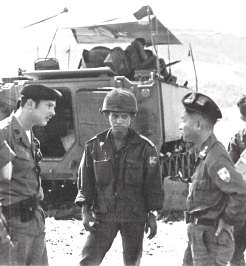

"During

the day ," according to ARVN Colonel Tran Ly Hung, commanding officer of

the 3rd Armored Cav, "you can drive a single jeep from Pleiku to the Mang

Yang and back without an escort."

U.S. advisor

confers with

ARVN

3rd Cav

commander

Photo credit: Baker

The

3rd Cav strings out its armored personnel carriers and tanks along the highway

to provide maximum coverage. Each tank and APC can provide mutual support in

the event of an enemy attack. Furthermore, the armor is backed up by artillery

stationed at strategic points along the road. At night the road is closed to

normal traffic. Bridges along the road are defended by Regional Force

outposts. There are also several permanent outposts, among them one at

Deadman's Curve and another in the Mang Yang Pass -- historically and

theoretically the two worst spots in the road.

A

Deadly Curve

Deadman's

Curve derives its name from the numerous casualties convoys have suffered

there. Located a few kilometers west of the Mang Yang, it is a sharp, S curve

that forces convoys to slow down and limits traffic to one lane. South and

immediately opposite

The

Mang Yang Pass itself is perhaps the worst ambush site with its steep walls

thickly covered with brush. In the area of the pass, hundreds of grey,

leafless tree trunks stand, casualties of the countless barrages and bombs that

have hit there.

"There

is always someone there," commented Captain Ralph J. Ferrara of the MACV

advisory team to the 3rd Armored Cav. "If we pulled out at night, that road

would no longer be there."

In

the morning the APCs and tanks search for the mines that the Communists have

planted along the shoulders of the road the night before. After they have

cleared the road, it is opened to traffic.

Military convoys along the road are monitored and in the event of an ambush artillery, armor, and helicopter gunship support can be called in within minutes.

The

Bahnar tribesmen still live along the highway in their wooden huts mounted on

stilts. Now their villages are defended by Popular Force units. Montagnard boys

play along the side of the road and bare breasted women with either a baby or a

basket strapped to their backs trek along footpaths on their way to market. An

old man squats stone-like beside the road holding up a carved, wooden

helicopter and waiting for a GI trucker or engineer to come along and make an

offer.

The

montagnards have proved to be an important element in improving the security of

the highway.

They

fill the ranks of the RF and PF units defending the highway bridges and

adjoining villages. They keep an eye out for Communist activities in the area.

"The people have been won over by the government," Ferrara commented. "I think this is the main reason the road is relatively secure."

The montagnards are

often targets of Communist terrorism.

The Communists here today are only strong enough to be an irritation albeit a painful one. They do not have the resources for a major attack now.

The

situation has changed considerably since 1954. It is now the Communists who are

outnumbered and outgunned. They are now the ones with a lengthy and unreliable

supply line. From the standpoint of the allied strength in the area, it appears

unlikely that the Communists will ever duplicate their victory of 17 years ago.

Radio relay

station on top of the Mang Yang Pass in 1971

Photo credit:

15th webmaster

NOTE: Many of the men from the 15th Artillery served on firebases on either side of the Mang Yang Pass. LZ Schueller was to the east, and Paul Hunter adds these memories:

"LZ Schueller was nearest PK 11 on the map in the article. As I remember it we were approximately 12 km west of An Khe. Our purpose in being there was to push the VC back in order to reduce the number of ambushes on the convoys heading west."

[More photos of the Mang Yang Pass]

TRAILBOSS

Reprinted from the

October 1971

"TYPHOON"

Courtesy

of: Pat Costello

Ten spinning tires

slap the asphalt of QL-1. They carry a silent but deadly cargo amid a

speeding convoy transporting supplies to one of the allied units

stationed throughout Military Region 2.

The ten tires roll beneath a U.S. Army 5-ton truck. About 3,000 pounds

of whispering thunder rests in the truck's cargo bed in the form of four

50-caliber machine guns paired over-under style on a single mount.

Easy Rider, Southern Comfort, American Breed, A Whole Lot o' Lead -- all are quad-50 machinegun convoy escort trucks that belong to E Battery, 41st Air Defense Artillery. This Tuy Hoa based battery, popularly known as the "bastard" unit of Second Regional Assistance Group Artillery because it totes 50-caliber machine guns instead of 105-mm Howitzers, provides convoy protection and perimeter security daily to 11 installations and firebases throughout Military Region 2.

With 25,000 square miles of every type of terrain imaginable for an area of operations, E Battery manages to keep pretty busy, according to Captain Thomas L. Baily, E Battery commander.

The number of convoy escort missions provided by the battery varies each

month. In June, three sections alone convoyed with 31 separate missions,

and sometimes the crews operated in a pinch.

"Hit 'em in the logistics," a general once said about the enemy. But before he said it, he made sure his own convoy teams were staffed with shutout pitching.

That's another way to say that they had little sham time. One crew, for instance, was called upon to provide protection for a two-day resupply convoy. When they arrived at the destination, the installation was on "red" alert and the quads took up perimeter security all night with double shifts. The next day, the quads escorted the convoy on the two-day return trip. Crew members ate and slept on their vehicles, sometimes performing weapons maintenance on the run.

How does the work load affect the morale of the quad-50 members?

Apparently the more work, the better.

"I've been real, real lucky so far," Baily said. "My men

take pride in their guns as well as in their missions. I've got E-5s

doing jobs that lieutenants do, and usually I don't get word about a

mission until it's over and they're calling in an after-action report.

"If they get clearance to fire on a mission, you don't have to ask

them twice. They'll spray hell out of everything," he added.

And what does it take to be a crewman on

the quads?

The members of Easy Rider-Southern Comfort section stationed at Camp

Wilson have most of the answers.

"A lot of guts and no brains," joked one of Easy Rider's

crewmen. He drew a few boo's from the rest of the two crews standing

around him.

"The quads can do anything if they have to," commented PFC

Mike Walsh from sister gun-truck Southern Comfort.

"There it is," chorused a few.

"I wouldn't want to be any other place in Vietnam but on that

truck. If I'm going to make it home, it will be because of that

truck," another chimed in.

"We just have to make sure everybody has his field jacket and pot

on. You've got to keep your sierra together."

Speaking was Southern Comfort's crew chief and section NCOIC, Walter

Miller of Montezuma, Ga. He was assigned to the quads in May, and

it didn't take long for him to adapt to the roadrunner pace.

"For every eight hours on the road, we usually pull at least three

hours of maintenance," he said.

"When we get above 10 per cent deadline," Baily added,

"all hell breaks loose. But until then, you don't hear anything --

good or bad -- as long as the trucks are running."

Photo credit: Cockson

Both statements partially reflect the importance placed on the fire support and shock effect that the quads make available. The enemy tends to stay away from the quads' sectors of fire in perimeter night defensive postions. And on the road, the brightly colored gun mounts are recognized as law 'n order badges rather than as easy targets by the enemy. There is a certain excitement, a natural feeling of confidence, that spreads over each quad crew on convoy escort missions.

And it is reassuring to them to wheel unhampered through a potentially dangerous pass with a convoy when only a week before another convoy without their escort was plagued with enemy harassing fire.There also appears to be a certain amount of respect for the 10-ton thunder-truckers among the friendly Vietnamese populace. Passing through the villages, Vietnamese adults silently watch the convoy roll on while the kids wave at all the vehicles. When the quads pass in review, the kids gape in awe and flail their hands more vigorously while the adults follow with their eyes the path of each quad until it is obscured from sight.

A day in the firebase is somewhat less exciting. The wind that blows a man's nose back against his face as he looks sidelong from the rear deck of a quad escort on the move no longer exists and the resulting heat is oppressive. When it becomes too dark to pull maintenance, guard duty is the only job left. It lasts all night.

But the chow is good -- at Firebase Wilson anyway. And Miller's crews do find things to do to pass away their free time. In the late afternoons, they can watch the Koreans stationed on the same perimeter lift heavy weights as though they were balloons on toothpicks. That's only a warm-up for an occasional Taekwando demonstration, judo Korean-style.

Or the enlisted men and NCOs from the artillery battery down the hill may bring their small arms weapons up to the test fire range near the Southern Comfort crew's hootch for some target practice at the mud puddles below them in the valley.

When Easy Rider and Southern Comfort get together for such an exercise, they create a firepower demonstration that brightens the twilight with trails of red tracers. The racket created by the spitting quads sounds like thunder from a marching band of a thousand snare drums. Each quad can lay down 2,000 rounds a minute.

The next day brings more weapons maintenance in the early morning hours.

Miller sees that it all goes well.

"I don't have too many command problems," he said.

"The people -- they respect me. I'm the only black man in the

section and I like to pitch in and work with the men myself."

He's the boss, but he also changes tires. The men acknowledge that he's

the section leader, and they call him "Miller" instead of

"sergeant." Miller prefers it that way. He also pulls a shift

on guard every night. And when he announces that a mission has just been

called in and the trucks have to be on their way to the start point in a

half hour, the crews don't have to be told to get with the action.

Southern Comfort and Easy Rider have never been late for a mission.

"Sometimes I wonder about these guys," Miller says. "They always want to get on the road."

And the whispering thunder rolls on.

Photos of two guntrucks

mentioned in the story above:

"American

Breed"

"A Whole Lota Lead"

More

guntruck photos

The following

article appeared in the March 25, 1971 ARTILLERY REVIEW, "an unofficial authorized

photo offset newspaper published monthly by the I Field Force Vietnam Artillery

Information Office."

By SP4 James V.

Durkin

6/32nd Arty IO

PHAN RANG - A handful of American missionaries and approximately 50,000 Montagnards are a lot happier and a little richer today, thanks to the donations of the men of I Field Force Vietnam.

On March 5, at the Evangelical Montagnard Training Center in Phan Rang, Colonel Robert J. Landseadel, Jr. presented Reverend and Mrs. Keith Kaiser with a donation of over 59,900 piasters, or $218.

The donation came from the collection offerings of I Field Force Vietnam chapels' Protestant services on February 14.

The Evangelical Montagnard Training Center was founded by the Evangelical Church of Vietnam, which is sponsored by the Christian and Missionary Alliance of North America. The Alliance has over 850 missionaries in 27 countries, and has been carrying out its work in Vietnam for over 60 years.

Primarily, the Training Center is intended to bring religious instruction to the Montagnard people, which is accomplished by teaching the tribesmen to read, mostly primers of Bible stories. It also serves as an instruction center for Montagnard ministers and pastors. There were about 400 pastors and 100 ordained ministers. It is also a gathering place for conferences of the pastors and ministers.

Reverend and Mrs. Kaiser have been in Vietnam for four years, and will shortly leave for a one year tour of the States and Canada, raising funds and searching out prospective missionaries. Their first four years were very rewarding, they say. Besides spreading the Gospel of Christ, they found each other. They met during the Tet offensive of 1968!

The money will be used to improve the existing facilities at the Center, to help build another guest house, and to help build a parsonage for the Vietnamese Pastor. Presently there is a church with room for 200, three classrooms, a missionaries' residence, and a guest house which will sleep 80.

The United States servicemen's presence has been a great help. "I wish the American people could hear more about us. You hear so much anti-military, but right here in Phan Rang, the Air Force has given us lumber to build three churches. We've easily been given $1000 from Army and Air Force units in the area," said the young missionary.

Reverend and Mrs. Kaiser are dedicated people involved in a worthwhile cause, and the men of I FFORCEV can know that their generous donations are being put to good use.

The following article appeared in the March 25, 1971 ARTILLERY REVIEW newspaper.

By SP5 Fred A. Hapak

5/27 Arty IO

PHAN RANG – Specialist Five Dennis Johnson, a Clinical Specialist assigned to the 5th Battalion 27th Artillery, recently treated a member of the 589th Engineer Battalion who was bitten by a Pit Viper.

The engineer was working in a maintenance shop when he moved a truck tire and confronted the 2-1/2 foot long Viper. The snake, which was identified as a Taiwan Habu, bit the engineer on the index finger of his right hand.

"If he had been bitten anywhere else, on the forearm for instance, the snake could have injected venom into the lower layers of skin and caused a more serious bite," related SP5 Johnson.

"Since the bite was on the finger, the snake could not get a good grasp," he continued. "In fact, the snake broke one of its fangs when it hit the bone in the finger."

The snake was killed and brought to the Aid Station with the patient ten minutes after the incident occurred.

SP5 Johnson, who had gained some experience with snake bites when he treated the victim of a s Rattlesnake bite at Fort Sam Houston, Texas, immediately checked and cleaned the wound and had the patient soak his hand in a warm solution. The wound area was then packed in ice and the patient given a Tetanus Toxoid inoculation.

Later in the day, as the patient was resting under observation in the 589th Hospital Ward, two younger Pit Vipers, about 12 inches in length, were discovered and killed in the same building. Two larger ones escaped.

The patient was released after two days and suffered no adverse reaction to the bite.

The following article appeared in the March 25, 1971 ARTILLERY REVIEW newspaper.

State Bonus Information

Seven states are currently offering bonuses upon completion of tour of duty in the Republic of Vietnam. The states and benefits now offered are:

CONNECTICUT

$10 per month not to exceed $300

DELAWARE

$15 per month stateside duty, not to exceed $225, $20 per month foreign duty, not to exceed $300

ILLINOIS

$100 lump sum; survivors $1,000

LOUISIANA

$250 after hostilities and an official statement by the President to that effect

MASSACHUSETTS

$300 for Vietnam duty; $200 elsewhere

PENNSYLVANIA

$25 per month not to exceed $750

VERMONT

$120 lump sum for Vietnam duty

VIETNAMESE LAWS

MACV Directive 58-1 para. 7a states, "Motor vehicle operators will obey all Vietnamese traffic laws and regulations and will comply with the instructions of Vietnamese police controlling traffic". Additionally, pedestrians are expected to respond to Vietnamese police traffic control procedures. It is imperative that all US personnel comply with local traffic laws and regulations. When a member of the US Armed Forces violates traffic laws and regulations, not only does the individual violating the law make a bad impression but this reflects poorly on the US Armed Forces and the United States. Remember, you represent the United States. Be a good example, obey the laws.

VEHICLE SAFETY

During Dec 70, 5 USARV vehicles were involved or allegedly involved in "Hit and Run" accidents. These accidents resulted in five fatalities and two serious injuries to Vietnamese citizen personnel. Fleeing the scene of an accident is a serious charge for which court-martial can be held resulting in a maximum sentence of a bad conduct discharge, forfeiture of all pay and allowances and confinement at hard labor not to exceed six (6) months. All personnel when involved in a traffic accident must stop, render aid to the injured and notify the Military Police. This is not only a legal obligation, but also a moral one.

PERSONNEL CLAIMS

This story appeared in the December 1969 TYPHOON magazine.

Kit Carson Scouts...

REBELS

WITH A CAUSE

By SP5 Tim K. Brown

"It's no damned wonder you always win," teased the American sergeant, as he scooped up his new hand of cards. "You always deal yourself first and then finish the rest of the table backwards."

Kit Carson scout Trinh Ban Bong acknowledged the chiding with a mischievous smile, looked at his hand and asked, "Can you open?"

Four card players surrounded the hood of a jeep which they were using as a table--two of them Kit Carson Scouts, formerly enemy soldiers, and two of them American soldiers. The cards were soiled and dog-eared and the stakes were match sticks.

After a round of bold betting, Bong took three new cards for his own hand before addressing the table.

"Cards?" he asked.

During the final round, Bong called to the power. His opponent spread a full house across the jeep's hood. Seeing he was beaten, Bong slammed his cards on the OD tabletop with such mock disdain that he sent match sticks and discards bouncing to the fenders and onto the ground.

Although Bong's nonchalance toward American poker rules may raise a few eyebrows, his ability at sniffing out the enemy for his American unit, the 7/17th Air Cavalry, 4th Infantry Division, will cause no one to call for a misdeal. He and nearlv 200 other Kit Carson Scouts, (KCS) are using their experience as former enemy soldiers to help the 4th Infantry Division defeat the VC and NVA in northwestern II Corps.

The Marines started the KCS program on a trial basis in the spring of 1966. Since that time, because of its success, it has become a nationwide program and a proven, effective way to second guess the enemy. Almost all American units that conduct tactical combat operations in II Corps are assisted by Kit Carson Scouts.

"Most of them have more or less grown up with this war," explained the 4th Division KCS project officer, First Lieutenant Robert E. Ponzo, New York City. "They have an almost instinctive ability for guessing what the enemy will do in a given situation. They know the enemy, they know the jungle, and they have made a definite political decision by changing sides."

Photo by: SP4 Cliff Woita

Formerly a VC sapper, Kit Carson Scout Tong Cong Nghiep demonstrates his enemy-acquired skill of going through the wire. In less than five minutes, he snaked his way through the barbed wire barrier without making a sound.

What motivates these men, whose

average age is about 23, to leave the ranks of the enemy to work for the allied forces is

a question often asked but seldom fully answered.

"The language barrier is one of the biggest problems in finding out why they change sides," inserted Captain Billy L. Weaver, 704th Maintenance Battalion. "Even with the English language training they receive before becoming a scout, it is difficult to have a conversation in depth with them. Our scout, Tu Duc, who is worth his weight in gold, was a VC guerrilla for over two years. What made him change his mind, we don't talk about. All that matters is that he does an outstanding job of saving American lives."

"Their record speaks for itself," added Lieutenant Ponzo. "In the past two months we have awarded two of them the Silver Star, which is the highest American medal for valor that the scouts are authorized to receive."

One of these scouts, Nguyen Thu, was walking point for his company, A Company, 1/14th Infantry, on a search and clear mission when they ran into a company-sized NVA unit. During the immediate exchange of fire, Thu was hit in the left arm and leg but refused to go to the rear for medical attention. The fire fight lasted for nearly an hour with the wounded Kit Carson Scout running from platoon to platoon pointing out possible enemy movement. Realizing that the enemy was about to out-flank his unit, he ran across an open, 25-meter stretch of paddy land to inform the company commander, who called in cobra gunships to stop the advancing enemy force.

During the fight mortars landed only a few yards from the commander's position and started fires which Thu beat out with his hands and feet. In doing so he received serious burns on his hands and arms but still refused medical attention. He then darted about 30 meters outside the perimeter and began yelling at the enemy, telling them to rally to the GVN. "Chieu Hoi, Chieu Hoi" were his last words before he was mortally wounded.

"The Silver Star was awarded posthumously," said Lieutenant Ponzo. "Dedication to duty like that has us all sold on the program. And they know what they are getting into before they become scouts. In the past year we have had four scouts killed, and I tell them that before they take the job. They know they will wind up with the point element of their unit, and still we get volunteers."

Each of the scouts joins the program on a voluntary basis. After rallying to the GVN, he spends about six weeks at the Chieu Hoi Center where he is given a political education and some vocational training. Upon release from the center he is granted a six-month draft exemption and can do as he chooses. Just prior to his release, recruiters like Lieutenant Ponzo introduce them to the KCS program. Those who volunteer are then given a personal interview by the recruiting officer and a Vietnamese interpreter.

"During the interview, I consider the man's experience as a soldier, his physical condition, and just generally how he responds to my questions;" Lieutenant Ponzo said. "Experience is probably the most important consideration: if a man was only a rice bearer for the enemy, his usefulness to us as a scout would be limited."

Once selected, the man goes through a two-week training period at the KCS training center in Pleiku, where he is given a basic course in English and introduced to U.S. weapons from behind the sights instead of in front of them.

The 42-hour block of English language study emphasizes military, tactical and survival phrases and basic vocabulary. A 12-hour block of organized athletics enables the training cadre to further determine whether the man will be able to keep up under the rigors of the field. Patrolling, ambush tactics, and a close look at equipment like miniguns and the helicopters are especially interesting to the former enemy soldiers.

The officer in charge of the training program, First Lieutenant Steven D. Carlson, Hingham, Mass., commented, "It's the first time most of them have ever seen a chopper close-up, and we get a lot of, 'Oh, number one' reactions from these guys who have learned to respect American weaponry the hard way. They usually have to work a little to master the M16 but they use the M79 grenade launcher as kind of a knee mounted mortar and catch on to it real quick; in fact, I'd say faster than most Americans."

The two-week training session ends with a formal graduation ceremony at which the scouts receive their distinctive KCS flop hats adorned with a 4th Division Ivy Leaf insignia on the front and an official KCS badge. An American buddy teams up with the scout and shows him around until he gets used to his new surroundings.

"At first, Duc was a little quiet and stand-offish," said Sergeant Douglas Carnegie, 704th Maintenance Battalion ambush patrol member, "but now he is just one of the crowd. We all have a lot of respect for what he says. If he says ‘number ten’ about something, that's good enough for us; we won't have anything to do with it. And when he gets scared, we do too, because he is a pretty hard man to shake.

"Sometimes it gets a little embarrassing. Like the other day we found what we thought was an entrance to a VC underground tunnel complex. Duc just laughed, dug down into the tunnel a few feet and came bounding back out of the hole followed by two porcupines."

In addition to their skill at fending for themselves in the.jungle, some of the scouts are using specialized talents learned from the enemy to aid and instruct U.S. troops. Ton Con Nghiep, a 21-year-old KCS, had worked with the Viet Cong for four years. Two of those years he spent as a sapper, learning to crawl undetected through the maze of tangled concertina wire that surrounds American bases throughout Vietnam.

"Nghiep has made believers out of many of our U.S. troops," said First Lieutenant Willie L. Henton, the officer in charge of the 4th Division Replacement Training Committee. "When we get new troops in, we have him give a demonstration on crawling through the wire. It never fails, he strips to his shorts and snakes his way through the wire without so much as budging a pebble inside one of the Coke cans that hang on the wire. When the U.S. soldier goes on bunker guard the next week he'll do a lot less daydreaming and a lot more looking."

Each scout earns 5000 piastres a month as base pay. He is entitled to the same advantages and treatment as a U.S. soldier, with the exception of PX privileges. He is clothed, housed, and fed as a U.S. soldier, receives the same medical attention and has a chance to work his way to higher pay scales based on his leadership ability, the same as the U.S. soldier.

His job as a scout lasts as long as he wants it to. He can quit at any time, and if he does not do his job well, his service can be terminated.

"Our attrition rate is relatively low," Lieutenant Ponzo boasted. "And the program is getting better all the time. I guess the word gets around about what we expect of them, so if they don't think they can handle the job, they just don't volunteer. This last graduating class of 19 scouts was probably one of the most physically fit we have ever had."

The youngest member of that class, 14-year-old Tran Van Hong, standing with his classmates after the graduation ceremony, was called to the side and asked how he felt about his new job as a Kit Carson Scout.

"Too soon to tell," he replied grinning, "but your C-rations sure don't fill me up." He saw his new American buddy motion to him that it was time to go and excused himself with a nod. Then with an impish nonchalance he put his hat on backwards and headed toward the truck.

This story appeared in the Summer 1969 UPTIGHT magazine:

By SP5 T.J. Mathews

Uptight Staff Writer

One year ago the little village of Plei Xo squatted in a corner of the Central Highlands like a forgotten child.

The tiny hamlet was only 18 miles southwest of the bustling city of Pleiku, but the farmers and charcoal makers of Plei Xo could not easily get into town to sell their goods. Commuting was done by man's oldest method -- walking.

Then the U.S. Army Engineers arrived in the area, cutting National Highway 9 west from Pleiku out past Plei Xo to the civilian irregular defense group camp and airfield at Duc Co. The Army built the road principally to supply their troops, but in the meantime that little hamlet attached itself to that asphalt highway and suddenly became open to the outside world.

Soldiers resurface a road with asphalt

Sturdy thatched homes and bright shops and churches now line both sides of QL-19 at Plei Xo. The farmers trade their produce with the people of Pleiku for some of the comforts of modern life. "You see more and more scooters and other vehicles traveling between the village and Pleiku," commented Major Clayton H. Carmean, operations officer of the unit that built the road.

"It just sort of snuck up on us," Lieutenant Thomas G. Lester, another engineer said, for the engineers had hardly noticed the village when they built the road. But the Army is not likely to overlook these little villages again as they push into one of the most ambitious road building projects Vietnam has ever seen.

There are plans for the U.S. Army Engineers in Vietnam to lay down 2,200 miles of paved highways. Before long a driver should be able to get behind the wheel and go from the Delta through Saigon through the Central Highlands and out to the shore of the South China Sea. If he keeps his eye on the road, he should be able to maintain a steady 50 miles an hour with hardly a bad bump.

The Army's engineers, aided by civilian contractors and allied units, are opening highways all over Vietnam near small villages like Plei Xo. Their big bulldozers are cutting across the flat, dry Central Highlands and sloshing through areas in the Delta quickly drained to make new thoroughfares. Engineer units are scalling down their military base improvement projects and hitting the roads in increasing numbers. "Right now, 51 percent of our efforts are involved in this road program," said Major Carmean, operations officer of the 937th Engineer Group, 18th Engineer Brigade.

"Look here," he said, pointing to a map of the northern II Corps area where the 937th Group is cutting its roads. "Here you have the heavily populated city of Pleiku, and here, to the north, you have Kontum. It's an awfully nice little town in an area that produces bananas, tea and coffee. We've been improving Highway 14 between these two cities and the civilian traffic between them is up to 2,000 vehicles a week, going both ways. Any time you have that kind of commerce both cities benefit."

"Now here, north of Kontum, is the Montagnard village of Kon Ho'ring. We've been extending the tactical road up past them to Dak To, and the Montagnards now use the road to bring their products into Kontum."

He pointed out that east-west traffic from the coast to Pleiku and back is also increasing as his men turn National Highway QL-19 into a Class A road. Military traffic still predominates, but the sturdy 23-foot wide road with 8-foot shoulders is being used heavily by all kinds of vehicles. In a recent week, U.S. military vehicles made 5,687 trips back and forth on the highway, while ARVN vehicles made 808 trips and Vietnamese civilians made 1,415 trips.

"One reason we're going to see more civilian traffic on these roads," Major Carmean said, "is that the enemy can't mine the road as effectively when it's paved with asphalt. It's much harder for them to emplace the mines so that we can't see them. And we can sweep the road much faster and easier because we can see the mines better. Thus, the civilians are much more confident about using these roads."

The new roads promise to frustrate the Communists just as much in the Delta. "Currently with no ready transportation for their goods to market, the farmers don't raise as much as they can and realize little profit for what they do raise," said Lieutenant Colonel Richard E. Leonard, commander of an engineer unit that is improving a section of National Highway QL-4, the sole land link between Saigon and the Delta.

The engineers all over Vietnam were racing against time to build as many miles of road as possible during the dry season and seal them water-tight with asphalt before the monsoon rains gave Vietnam its yearly soaking. If water gets into the rocks and packed earth that make up the base of these roads, they will begin to deteriorate immediately and be useless by the time the dry season arrives again.

But the engineers were winning the race, with the help of a bonus in heavy construction equipment -- $18 million worth of it bought off the shelf and shipped to Vietnam to give the accelerated road building program an extra boost.

"This new equipment was a tremendous help to us," Major Carmean said. "The rock crushers, rollers and other equipment helped us improve both the speed and the quality of our construction."

With all the new equipment came new experiments in road building to meet the unusual engineering challenges of sub-tropical terrain. For instance, the 36th Battalion was trying to lay one section of road through an area that was under water.

"At first the natives were very skeptical of the whole thing. Then when they saw our bulldozers working in the paddies they were dumb-founded -- they couldn't believe they were floating," Major F.H. Griffis, battalion operations officer said.

Cleverly using dikes and improvised upriver tide tables, the Delta engineers were able to drain the area down to a heavily soaked layer of mud and clay. They stripped that off and laid down layers of compacted clay, then layers of clay and lime that chemically react together to stiffen the base. Finally, cement was mixed into the clay-lime as a top layer and the road was sealed with asphalt.

An earthmover distributes

lime on a Delta

roadbed, leaving a trail of white dust

"The clay-lime stabilization technique we are using here has never been tried on a large scale," Lieutenant Donald Wolf, construction officer for the 36th Battalion, said. "It has been used for small patches on highways in the U.S. but never on anything as big as this."

In the Highlands, the engineers also insisted on making their construction as permanent and solid as possible. "Supporting this bridge are 42 piles driven 20 to 30 feet into the ground," Platoon Sergeant George W. Sampson stated as he watched his men of the 3rd Platoon, Company B, 20th Battalion, 937th Engineer Group pour cement into forms for a bridge abutment on QL-19 West. "This keeps the concrete from shifting and helps distribute the weight of anything going across the bridge. You know, as concete ages, it gets stronger. This bridge will last anywhere from 50 to 75 years before it starts deteriorating."

Barring major calamities, the bridges and hard-surfaced roads will continue to be built at a rapid pace. The Vietnamese will reap the benefits of this network of highways for years after they are completed. "While these roads are listed as line of communication projects, I believe they are the largest civic action project in Vietnam. The potential impact on the Vietnamese economy is tremendous," Colonel Leonard said.

"These roads will make friends," Major Carmean predicted, "and in the long run, when the fighting lets up, they are going to help improve the Vietnamese economy almost overnight. The Vietnamese will be able to get around so much better and that will have an enormous effect on everything."

This story appeared in the August

1969 TYPHOON

By Sp4 Tim K. Brown

A veneer of red highlands soil, ground into powder by the churning tracks of

tanks, covered the men, machinery, and heavily sandbagged buildings of Fire Base

Blackhawk, 20 miles east of Pleiku. The 2d Squadron, 1st Cavalry, had operated out of the

firebase for nearly two years, patrolling Highway 19 from the Mang Yang Pass west to

Pleiku and north on Highway 14 from Kontum to Dak To.

Now the cavalry unit prepared for a 300-mile journey to a new area of operations. The squadron was moving from the operational control of the 4th Infantry Division to Task Force South, the American command responsible for the southern area of II Corps. For the troopers of the 2d Squadron it would mean a new climate and a new terrain but a familiar mission: clear and secure a road vital both to the war effort and the civilian economy.

Tanks and armored combat assault vehicles (ACAVs) crowded the inside of the perimeter of Firebase Blackhawk. All three line troops were there, jammed into a maintenance area that usually held only one troop at a time while the others worked the roads. Within three days the first of the armored mobile homes would begin the journey. The old tensions and anxieties that went with daily ambush patrols and road security positions were replaced by the pressure of preparing for the move.

The Cav would travel east on highway 19 to the coastal city of Qui Nhon, where the vehicles and their drivers would be loaded on ships and transported more than 250 miles to the southern II Corps city of Phan Thiet. The remaining crew members would travel ahead of their vehicles by air.

The Cav's new job would be to clear and secure a treacherous 100 mile stretch of Highway 1 running from the III Corps border north to Phan Rang. For years enemy ambushes had restricted both military and civilian travel. The Blackhawks would be starting from scratch, and would no longer have the intelligence help from local villagers on whom they depended in their old area of operations. It would take time to gain the trust and respect of the Vietnamese inhabitants of the area, most of whom had little experience with American troops.

The squadron is made up of five troops: three line troops, manning tanks and ACAVs; a headquarters troop; and an air cavalry troop which had been assigned to the 1st Brigade of the 4th Infantry Division, operating out of An Khe, about 30 miles east of Firebase Blackhawk on Highway 19. The line troops would move out at one-day intervals.

Charlie Troop was the last to join the waiting squadron at Firebase Blackhawk after returning from an ambush patrol just south of Kontum. Specialist 4 Thomas R. Prince, a mortar track gunner from Ann Arbor, Mich., recalled the fight while he prepare his equipment for the move. "We lost three men and that's always bad," he said as he pulled the soot covered rag from his mortar tube. "But I guess the action was a good tune-up for what’s to come."

The men were briefed on their new AO and the country they would cover on the road to Qui Nhon. Keeping their vehicles and weapons in top battle condition is a routine operation for the Blackhawks, and now the prospect of facing unfamiliar territory made their maintenance chores seem even more important.

Charlie Troop, accompanied by the medical, communication, and maintenance sections of Headquarters Troop, was the first to move. At 8:30 a.m., May 29, they rolled out of Firebase Blackhawk for the last time. The armored column stretched along Highway 19 for two miles. The troopers pushed east over the Mang Yang Pass, a graveyard for more than 2,000 French soldiers who died in fighting along the road. Their grave markers at the summit of the pass, a familiar sight to the cavalrymen, were hidden by a low cloud cover.

As they lumbered through, the soldiers’ thoughts turned from the French tragedy to hopes for a safe arrival at the day’s destination, the camp of the 160th Heavy Equipment Maintenance Company (HEM), about 20 miles west of Qui Nhon. The territory beyond the Mang Yang Pass was new country for the cavalrymen. Their usual visual diet of highlands bush country and simple Montagnard villages was replaced by the flat farm land and scattered Vietnamese villages along the route to the coast. Early in the afternoon, Charlie Troop pulled into the maintenance yard of the 160th HEM Company.

Within 30 minutes the men were cleaning and checking their vehicles. This was the last chance to put the Cav machines in top condition before boarding the ships that waited in Qui Nhon harbor. The tanks and ACAV’s that could not be put into shape were replaced by new or rebuilt vehicles. The mechanics of the 160th and the cavalrymen worked carefully but quickly, knowing that the success of the mission, at this point, depended on how fast they could recondition the squadron’s vehicles.

The Colonel John U. D. Page, an Army ship, and six Navy LSTs (Landing Ship, Tank) waited in the Qui Nhon harbor to carry the Cav to Phan Thiet before the semi-monthly high tide was lost. The heavily loaded craft needed the deep water of the high tide to get close enough to the beach to unload their cargo. Failure to meet this tidal deadline would delay the trip more than two weeks. With this in mind, and knowing that Alpha and Bravo troops would arrive within the next two days to further congest the maintenance areas, the inspection teams and the men of Charlie Troop worked steadily into the early morning hours.

It's a big job for everyone, but it's one that must be done," said Chief Warrant Officer 3 Joseph Williams, Grand Ledge, Mich., of the 160th. "We would rather do the maintenance here than have them break down somewhere out in the bush. And besides, we're not doing half as much as the men of the Cav. Just take a look around you."

The 160th maintenance yard was alive with the discordant clanks of metal against metal, the heavy smell of oil and solvent, and the earnest voices of active tank and ACAV crew members. Engines were pulled and repaired or replaced. Hydraulic systems were overhauled, and tracks and transmissions were dismantled, repaired, and reassembled. Even so, some of the battle-weary machines would not continue with the squadron to Phan Thiet.

The squadron would leave Qui Nhon with eight new tanks, five new ACAVs, and one new mortar carrier, all of which had to be uncrated, assembled, and modified for Vietnam warfare. The 50-caliber machine guns, normally mounted inside the tank commander's armored cupola, were removed and externally mounted. "Moving the 50 gives the tank commander much more flexibility in his rate of fire," explained Specialist 5 Frederick M. McCarty, Tucson, Ariz., a tank gunner. "It is mounted inside as an anti-aircraft gun, and thank God we don't need that. Anvway, Charlie is pretty scared of it. There isn't much it won't fire through, and we like to get the most we can out of it."

Metal plates that slope downward at the ends of the tank's fenders, built to protect the top of the tank from the mud thrown up by the churning tracks, were cut off. "We’ll take the mud," said Specialist McCarty. "The jungle terrain will bend the plates down anyway and interfere with the movement of the track. In our job it’s more important to be mobile than clean." Additional gas-can brackets are mounted on the rear of the tanks, and large, empty ammunition cans were fastened around the turret for storage of personal belongings.

The squadron's vehicles rolled in and out of the 160th maintenance shop for three days. After putting their machines through the gauntlets of inspection and maintenance, some of the cavalrymen rested. Private First Class Lin Bell, a tank gunner from Eugene, Ore., sat on a cot beside his battle-ready tank. Now he had time to think about the mission that lay ahead. "I'm a little scared," he said. "Everyone is frightened when they get shot at, even in a tank, and we all have a pretty good idea that Chuck is going to be there to greet us. Even so, I'm ready to go. Being cooped up here in this motor pool is working on my nerves."

At 6 a.m., three days after they arrived, Charlie troop left the 160th. The early morning sun silhouetted the Vietnamese towns scattered along the remaining strip of Highway 19 as the tanks and ACAVs pushed toward Qui Nhon harbor. Three hours later the vehicles were sitting close together, waiting to load on the John U.D. Page.

The Page's massive loading ramp was lowered, connecting her 338-foot deck with the beach, where more than 50 tracked and wheeled vehicles and their drivers waited to board. By noon, the bulky machines bad been wedged into position and chained to the deck. The Page set out with her 9,000 tons of cargo, leaving six smaller Navy LSTs waiting in the harbor for Bravo and Alpha troops. The Page's The Page's massive loading ramp was lowered, connecting her 338-foot deck with the beach, where more than 50 tracked and wheeled vehicles and their drivers waited to board. By noon, the bulky machines bad been wedged into position and chained to the deck. The Page set out with her 9,000 tons of cargo, leaving six smaller Navy LSTs waiting in the harbor for Bravo and Alpha troops.

"This is what the Page was built for," said the suntanned skipper, Chief Warrant Officer 3 Fred C. Ryle, Newport News, Va. "It's what we call a 'ro-ro' mission, meaning roll-on, roll-off." Shuttling priority cargo along the coast of Vietnam keeps the ship's deck loaded with a variety of war supplies, ranging from bombs and ammunition to food and clothing. Now underway, and well ahead of the semi-monthly tidal retreat on June 6, Mr. Ryle turned his attention to the daily tide. "Without the help of the daily high water we'd have to anchor out a full day after reaching Phan Thiet. Under normal conditions the extra day at sea would simply be an unwelcome delay, but it is even more important that it be avoided on this trip."

Six more ships would arrive within the next two days and use the same narrow strip of beach for landing. If the Page could hold an average speed of 10 knots, she would arrive at her destination at 1 p.m. on June 2, a comfortable three hours before the retreat of the daily high tide.

The cavalrymen aboard the Page left the nautical problems to the ship's crew, and made themselves comfortable even though the deck of the ship was so crowded with machinery that a walk from one end of the ship to the other meant jumping from vehicle to vehicle. Poncho liners, tied to the vehicle antennas, formed a shade canopy across the rows of tracks. Cots and sleeping bags worked their way into the ship’s obscure corners, providing refuge from the hot, metal deck. The bellies of the tanks and ACAVs had been well-stocked with C-rations and soda, and meal time was whenever the men were hungry. For a day, the Blackhawks had a chance to put their feet up and let someone else worry about getting them there.

At 2:30 p.m. on June 2nd, 26½ hours after leaving Qui Nhon, the ship's loudspeaker carried the skipper's familiar voice, this time not to the crew, but to the cavalrymen: "Gentlemen, we are about 45 minutes outside of our destination. Please prepare yourselves and your vehicles for landing."

Unfavorable winds had slowed the Page to an average speed of 8.5 knots, and she had lost almost two hours of valuable high tidal time. The battle machines still chained to the ship's deck would have to be unloaded quickly, without incident, in order for the Page to back off the beach ahead of the tidal retreat.

The Cav's 9,000 tons of

men and machinery clear

the Page's deck. The unloading took just over

30 minutes, giving the ship ample time to return

to deep water ahead of the tidal retreat.

The drivers and vehicles were rejoined by their

crew members who had traveled ahead by air.

This was the first beach landing for many of the cavalrymen, but it seemed like a well-practiced, everyday occurrence. The men and the 9,000 tons of machinery cleared the ship's deck and rolled onto the Phan Thiet beach in only 30 minutes.

The Page quickly slipped away from the beach and into deep water, as the Blackhawks moved inland to their, temporary tactical headquarters in a sandy open field south of the city. The drivers and vehicles were rejoined by the crew members who had arrived a day earlier on C-130s. Now Charlie Troop waited for Bravo and Alpha troops and prepared for their trek along the dangerous stretch of Highway 1. Maps of the new AO had been thoroughly studied before the men left Firebase Blackhawk, and with that education behind them, the Cav wanted a first-hand look at what they faced. A helicopter reconnaissance trip took two key officers north along the highway to Song Mao. The village would eventually be the Cav's tactical operations center. The visual reconnaissance confirmed earlier reports of heavy enemy activity. A roadblock of fallen trees had been set up only a short way outside Phan Thiet. A rebuilt bridge rested on the crumpled wreckage of its predecessor.

This rebuilt bridge stands

above the wreckage

of its predecessor north of Phan Thiet on Highway 1.

The road, once vulnerable to enemy sabotage,

is now patrolled daily by the troopers of the 2/1 Cavalry.

During the troop briefing that followed the reconnaissance trip, Charlie Troop's commander told his men what he had seen and what changes to expect. "We’re going to have to start this one from the hip, slow and easy," he said. Instead of the congested bamboo jungle of the highlands, the Cav would operate in flat, open shrub-covered land broken by sporadic patches of triple canopy forest. The land would be unfamiliar, the local villagers would be new to the cavalrymen and their AO would extend over three times as much road.

These thoughts of change only whetted the Cav's desire to start. The cramped living conditions of the past 10 days had made the men restless, eager to return to the freedom and challenge of the road. "It's a new country for us," said the commander, ending his briefing, "but we’ll get the job done."

And the Action Was Waiting . . .

After only two days at its new firebase 40 miles south of Phan Rang, Alpha Troop was called to reinforce an ARVN company in contact. Led by Captain Robert Witton, Park Forest, Ill., the troop responded quickly by pouring 90mm tank rounds and 50-caliber machine gun fire into the NVA positions, killing seven.

Three days later, Bravo and Charlie Troops were securing the southern sector of the squadron's AO when they drew fire from an estimated company-sized force of would-be ambushers. The enemy was ill-equipped to slug it out with the Blackhawks' tanks and armored vehicles. B40 rockets, grenades, and AK-47s were no match for the Cav's sophisticated arsenal.

7/15th VIETNAM HISTORY

______________________________________